Advances in artificial intelligence could help alleviate bottlenecks within increasingly capacity-constrained terminal security. What do industry experts believe will be the most important benefits, and what challenges lie ahead? Alex Grant recently examined five key applications in a feature first published in the September 2023 issue of Passenger Terminal World magazine.

Demand for air travel is booming as the world’s economies recover from the disruption of Covid-19. The ICAO Council predicts that passenger volumes will return to pre-pandemic levels during 2023 and the industry is optimistic about further growth. According to IATA, annual demand is set to double to eight billion passengers in 2040 from four billion in 2019, putting pressure on already strained airport capacity.

AI-based solutions could become a useful asset for easing those pressures, and investment is ramping up as developers explore potentially lucrative commercial applications. Financial services firm UBS recently noted that AI has become one of the technology sector’s fastest-growing segments, adding that investors have recognized that today’s hype isn’t a ‘bubble’ and projecting that the industry will grow from US$28bn (€22bn) in 2022, to US$300bn (€236bn) in 2027.

Importantly, as independent safety and security consultant Donald Zoufal of CrowZnest Consulting explains, this isn’t a far-off technology and organizations are often unaware of the role it already has. License plate recognition, for example, is widely used to monitor traffic and parking areas at terminals, but AI could also help streamline the security screening process and improve the passenger journey.

“The choke points are the bag-drop checkpoints, and airports and airlines are piloting those biometric solutions to help move that process forward,” Zoufal says. “One of the first things I suggest you need to do is understand if you’re really using it. AI is out there, and you’ve probably already been using it for years. It’s important to understand what systems you are using and open the hood to understand what’s inside those black boxes.”

Streamlined identity checks

Passenger processing is one of the most familiar applications for AI in terminals, and it is delivering efficiencies. Dubai International Airport introduced 122 smart gates in 2019, enabling passengers to register in advance for face and iris recognition and complete passport control procedures in five seconds. Despite passenger volumes increasing by 161.9% (to 27.9 million people) during the first half of 2022, 97% of them queued for less than five minutes and 96% waited less than three.

IATA’s One ID program is advocating specific protocols for sharing passenger information in advance, then using biometric identification to offer seamless processing at the terminal. Airports are not required to employ specific tools, nor AI, but the latter could be complementary. Matthew Vaughan, the organization’s director of aviation security and cyber operations, says that airports and governments are both keen to make screening and facilitation less burdensome.

“There are processing systems behind advanced passenger information that are not only automating but also helping authorities develop better targeting of individuals who require secondary inspection,” Vaughan says. “Some jurisdictions are getting much better at that, because the nature of conversations they’re having with people coming across the border is really straightforward.”

However, Zoufal adds that airports deploying AI-based facial recognition solutions also have to be mindful of proven bias in the algorithms. Machine learning relies on input data and can struggle with minority groups, for example, where there is less data available. This could still require extra steps in processing some passengers.

“These algorithms are going to have bias, just like any human decision maker is going to have bias,” he comments. “Which bias is better? With the machine’s bias, the error rate is a math formula, and I don’t have that same math formula for a human. My guess is that the error rate is often going to be lower for the machine than it is for the human.”

Better baggage screening

Screening cabin baggage is a security critical process, but the large list of prohibited items and two-dimensional imaging mean it’s also complicated and time-consuming. Although CT systems have reduced the need to remove electronics and liquids before scanning, Alan Tan, SVP of aerodrome safety and AVSEC at Changi Airport, notes that there are still hurdles to overcome.

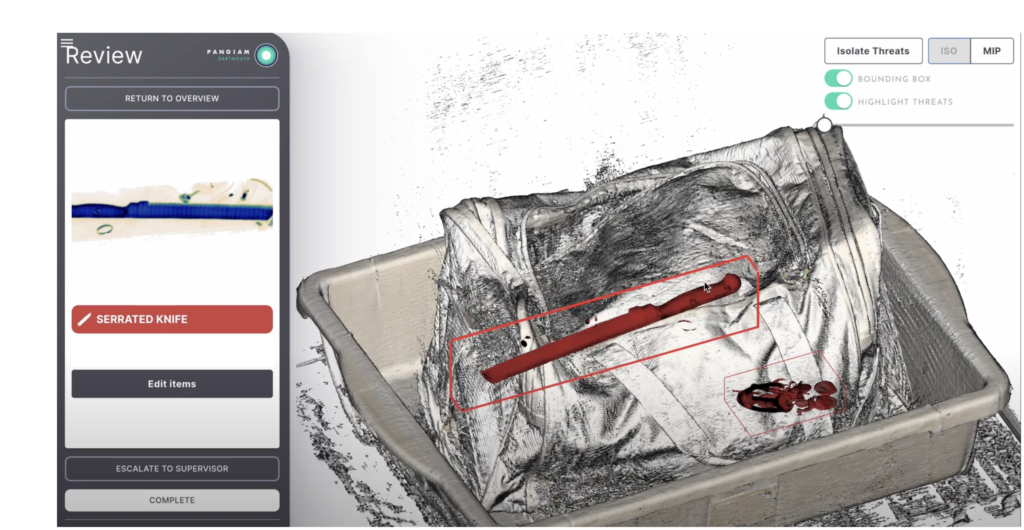

“The CT x-ray generates a 3D image and provides a lot of information for the operator to analyze,” he says. “This generally increases the image analysis time taken by operators. Automated prohibited-item detection systems (APIDS) could help to reduce the image analysis time and improve the speed of clearance at the checkpoint. Even if an APIDS is used with conventional 2D x-ray images, it could also similarly improve the speed of image analysis when APIDS move from an assist mode to self-clearance as the technology matures.”

Regulations are setting foundations for wider adoption. The EU has approved three standards for APIDS algorithms, and ECAC has developed testing protocols for fully automated applications.

Airports conducting trials include Schiphol, which is using the Project Dartmouth algorithm developed by security company Pangiam and Google Cloud. Project Dartmouth is powered by Google’s suite of computing services, AI, machine learning and computer vision. Designed to be compatible with existing scanners, it’s claimed that it can not only detect prohibited items but also use the data-mining capability of AI to identify anomalies and unusual patterns that would suggest a coordinated attempt to breach security. Subject to regulatory approval, Schiphol plans to trial the technology in a live environment.

Tan believes that further machine learning will help: “The detection threshold and increasing items that the APIDS need to detect will affect the number of false alarms.

As such, the better use of APIDS in the future would be to train it to not only detect threat items but also to recognize benign items.

“With machine learning, the known benign item list will become longer and unknowns will be reduced to lessen the need for rechecks if the bags have no threat items. With a large list of known threats and benign items, it could also have the capability of detecting emerging threats when unknown items are flagged.”

Improved working conditions

Like many emerging technologies, accelerating interest in AI has triggered concerns about its effect on the workforce. A recent report by the UK’s Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggested that 27% of jobs are at risk due to automation, including AI. However, its 2022 survey of finance and manufacturing sector workers found that 63% were happier in their role since they began using AI technologies, and over half said their mental health had improved.

Billy Shallow, senior director of security, innovation and technology at ACI, believes that security staff could experience similar improvements as more advanced screening solutions are rolled out. “APIDS algorithms can be used as an extra pair of eyes, but when fully developed in the future they have the opportunity to automatically conduct image analysis, with a human conducting alarm resolution,” he explains.

“This frees up screeners from doing repetitive and monotonous tasks to focus on risk and alarm resolution. A security screener has more than 100 items to detect on the prohibited item list, so the stresses and pressures can be quite challenging.”

Changi Airport’s Alan Tan agrees, adding that the interface between APIDS algorithms and human operators and their responsibilities is an important topic to address, potentially leading to uneven adoption across the world.

“APIDS will be a game-changer for security screening as travel demand will continue to increase but manpower supply will continue to be a challenge,” he says. “With such automated screening, demand for more operators could be better managed. The role of the operator will still be required as there will be emerging threats, and immediate threat resolutions are needed at the checkpoints.”

Monitoring the terminal

At Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, executive vice president of operations Christopher McLaughlin sees plenty of potential for AI in the context of one of the world’s busiest terminals. He believes that applications go beyond passenger and baggage handling, including automated threat detection in the terminal and identifying objects that threaten traffic on the runway, as this also impacts passengers.

“The sky is the limit for us,” McLaughlin says. “We are currently working on four large-scale projects that will be introduced in the next 12-18 months and are all heavily dependent on AI/ML. One is public-facing and three represent unseen layers of security that will work in the background, quietly improving security and the passenger experience.

“We believe that the future of aviation security is about setting up humans to do their best work by equipping them with smart tools that can solve historically challenging security problems. Doing this well, in every area where we see an opportunity, streamlines our customers’ experience, improves our security officers’ focus, and expedites our ability to respond to critical situations.”

Schiphol in the Netherlands is using AI to monitor the apron. Its Deep Turnaround system uses a camera to detect 70 events during the turnaround process, predicting delays up to 40 minutes before off-blocks time based on live and historic information. The aim was to improve turnaround punctuality and avoid the need for additional stands, but it has also formed the basis of a system providing live baggage tracking – from aircraft to reclaim belt – for passengers.

IATA’s Vaughan says there are also applications for detecting perimeter breaches, citing recent climate activist protests at airports. “There are plenty of vendors and technology companies that are helping airports in perimeter detection, controlling staff access points and suchlike,” he comments.

Optimized passenger flow

AI offers an unprecedented ability to analyze the way passengers move through the terminal, and particularly at security checkpoints. Dallas-Fort Worth introduced line-wait technology in 2018, using 3D optical sensors to anonymously track queue movement, ticket checks, screening times and re-composure based on heat and movement. Passengers are then notified of forecast waiting times at checkpoints, including how long it takes to walk to another one, and the former is updated every minute.

“Our goal is to provide our customers with transit information from parking garage to gate using AI/ML,” says McLaughlin. “By tracking and predicting passenger flow we can eliminate the stress that affects passengers due to having no control over the process. This application is also being applied to our line waits at specific concessions to provide more real-time information to passengers so that they have more control over their journey.

“AI/ML also influences certain aspects of the passenger journey that are likely invisible to them. For example, we recently introduced new exit-lane technology between sterile and public areas that has improved our security while also facilitating a more predictable egress experience for passengers.”

There are also operational benefits for airports monitoring passenger traffic. AeroCloud Optic, which launched earlier this year following airport trials in the UK and the US, uses computer vision to anonymously track passengers as they move through the terminal. It can trigger alerts if bottlenecks develop at security checkpoints, helping operators predict and plan for future scenarios. It also helps get passengers to retail areas more quickly, which has a commercial benefit.

Known unknowns

Civil aviation regulations are conducive to conducting trials of AI-based systems, notes IATA’s Matthew Vaughan. Rules tend to focus on outcomes and offer enough flexibility for airports to innovate, but this could also mean that approaches will differ across the world.

“Machine learning does have a role to play. What is preventing this from full adoption is the marketplace itself,” he says. “We’re talking about multiyear capital investment requirements, and a whole range of basic funding models influence the degree to which airports employ this kind of innovation and technology.”

Donald Zoufal notes that gaps in the regulations could also present challenges for adoption. He highlights the EU’s AI Act, which is due to be agreed by the end of the year. This is the world’s first comprehensive law governing the use of AI, regulating – or banning – specific applications based on their potential harm to users and ruling that systems should be overseen by humans instead of being fully automated.

“The global nature of air travel means it could set a precedent for other regions,” he warns. “Airports are concerned generally about privacy issues. Then there’s this concern about this unknown potential body of regulation that may come down the pike. They could spend all sorts of money and develop or buy this or that AI, only to find that two years from now they can’t use it because a statute has been passed to prohibit them from using that technology.”

This article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Passenger Terminal World. To view the magazine in full, click here.