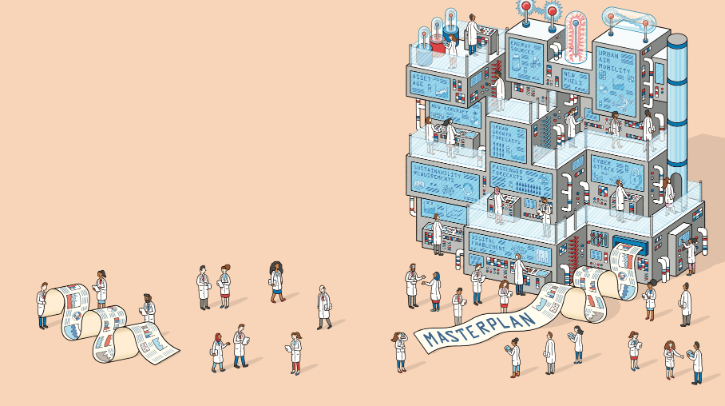

An airport masterplan should provide a clear roadmap for efficiently meeting forecast traffic demand through to the development horizon while preserving the flexibility necessary to respond to changing industry conditions. The time has come for airports to move on from mere ‘predict and provide’ masterplanning to something more futureproof.

Airports without fully conceived masterplans that take into account future requirements risk developing infrastructure enhancements that are incompatible, incorrectly sized, poorly located or underutilized, resulting in wasteful capex or restrictions on overall capacity, as well as potential challenges in the courts relating to sustainability commitments.

“In a nutshell, the masterplan is the vision for what the airport will look like in the future, from a space planning and infrastructure perspective,” explains Ross Dickie, head of masterplanning at London Heathrow Airport. At Passenger Terminal Conference in Frankfurt later this month, he will lead a discussion on how masterplanning is changing.

Moving target

Traditionally, airports have produced masterplans on a ‘predict and provide’ basis, with the forecast demand triggering the need for additional capacity development. At this year’s conference, Dickie will argue that this historical approach to masterplanning needs to broaden to accommodate factors such as existing asset age, sustainability objectives and future forms of aviation, to ensure greater robustness in uncertain times.

During his presentation, Dickie will explain how Heathrow has sought to identify new trends and issues, understand how these might affect the airport and work out how the masterplan needs to flex to take advantage of or mitigate them.

“If you look back at how masterplanning has traditionally happened, it’s been quite formulaic and linear,” he says. “You would develop a demand forecast to then work out what capacity you need to serve that demand forecast, and then tailor the masterplan accordingly.”

However, in the post-pandemic world, there are now many other factors airports must consider. “Even if you’re not in a world of continuous passenger growth, where the forecast demand doesn’t require a huge extension to your airport, your masterplan will need to take account of the impact of sustainability, operational efficiency and passenger service objectives on existing, aging assets,” explains Dickie.

“There is a whole range of factors that need to come into play that will inform what you need to be doing in your masterplan, which are not directly related to serving X millions of passengers per annum,” he continues.

Masterplanners need to pay particular attention to how best to decarbonize their facilities. “This will be an important driver for a masterplan, impacting space planning requirements,” advises Dickie.

“An airport may need to factor in a district heating system or thermal store, which they may never have previously had; they may need to change the way the airport is plugged into the national electricity network, because it’s likely we are going to need more electricity to achieve our net zero goals; or they may need to do something fundamentally different in how they supply and manage water,” he continues.

“The actions required to meet sustainability objectives can be very space hungry. The masterplan must therefore recognize these requirements, rather than just focusing on the number of passengers projected to go through terminals in the future.”

Build back better

During his presentation at Passenger Terminal Conference, Dickie will be joined on stage by Andrew Gibson, aviation global market director at Jacobs. With over 35 years of experience in the design, construction and planning of airports as both client and consultant, Gibson also lectures on masterplanning at the UK’s Cranfield University.

“In aviation, we’ve always felt we’ve had an intrinsic right to grow the industry by increasing passenger numbers and expanding our airports,” he says. “In recent decades, we have also had to consider sustainability and respond to it, to ensure we get license to continue to grow.

“However, now the industry is starting to address net zero and carbon reduction, it’s not enough to simply just mitigate our impacts, with license to operate conceivably becoming an issue. Even if an airport never grew, it would still need a masterplan because it would need to replace and renew its assets while bringing in new features and infrastructure that would have a physical impact on the airport, all of which the masterplanning team would need to predict and manage.”

“It’s not enough to simply just mitigate our impacts” Andrew Gibson, Jacobs

Gibson notes that during the pandemic there was much talk from the likes of US President Joe Biden and then UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson about ‘building back better’. “For airports, initially this was very much focused on net zero and carbon reduction – but is that all it should mean? Is that the only thing that’s changed?” he asks.

Taking a wider view, Gibson suggests an airport masterplan now also needs to consider climate response. “For some airports, that’s about resilience,” he says. “It’s about the implications of changing temperatures. We’re seeing flood events and rising sea levels that we’ve probably never taken account of at airports before.”

Major technological trends within society must also be factored in. “Take digitalization, which offers up all sorts of potential economies of scale and efficiencies for airports,” continues Gibson. “However, the more digital we are, the more susceptible we are to cyberattack. And while we were all working from home, we became more digitally enabled and we shopped a lot more online – does this mean that the way in which we sell commercial products at airports is going to change, with fewer shops and more digital enablement, so perhaps terminals don’t have to be so big? Or does it mean that the space we’ve got can be reconfigured? I don’t think we know the answer yet. However, we know that those pressures are coming because of changing buyer behavior and technology. All these things need to be taken into consideration, whereas 20 years ago it was primarily just passenger forecasts.”

Fuel for thought

When asked to name one trend or shift that could really affect the future of aviation, Heathrow’s Dickie pinpoints the potential switch to hydrogen-powered flight as being particularly disruptive.

“Heathrow is over 75 years old, and every aircraft that has ever used the airport has, to date, used the same type of fuel,” he says. “Use of sustainable aviation fuels is increasing but this doesn’t require any change to infrastructure. However, we now face a future where there might be multiple types of fuel. When we think about bringing hydrogen into an airport, although it may not have much of an impact on the passenger journey itself or within the terminal, it is clearly going to have huge implications for the wider real estate and it is going to have a very tangible impact on the marketplace.

“We now face a future where there might be multiple types of fuel” Ross Dickie, London Heathrow

“Let’s take how we get the hydrogen to the site. Will it be similar to aviation fuel, which currently comes in via a network of pipelines? If so, it is going to need to come in as a gas and then be liquefied on-site. How much power is that going to take and how much space is that going to need?

“Once liquefied, it must be kept at an extremely low temperature, but how do you then supply it to the aircraft stands, given the current standards are based on aviation fuel? It’s hugely space hungry. It’s hugely infrastructure hungry. And it is hugely uncertain in terms of the proportion of aircraft that might use hydrogen at an airport like Heathrow – it could be a very small percentage or it could be a very large percentage. This is the masterplanning challenge – we must plan for the infrastructure that’s going to enable the phased implementation of hydrogen operations, so even if we have the same number of aircraft and passengers as we have today, the impact is clearly going to be substantial.”

Vertical vectors

Urban air mobility (UAM) is another disruptive force that masterplanners must factor in. In January, the UK Civil Aviation Authority launched a consultation on design proposals for vertiports at existing airfields, paving the way for electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft operations in the UK.

“Every airport is looking at how urban air mobility might be integrated with their operations, the services it might provide and whether eVTOLs can be integrated with existing aircraft operations without unacceptable impacts, which is far from being a given,” notes Gibson. “There is little doubt that UAM has an exciting role to play in the future of urban mobility. The question is whether this is at airports with their complex and congested airspace.”

Dickie says, “The Heathrow runways are among the busiest in the world. While we’re following the UAM industry with interest, we would need to ensure that any UAM developments don’t compromise runway capacity.”

Despite all the challenges and potential scenarios, Dickie believes masterplanning is easier than actually delivering a major airport upgrade: “In many ways, producing a masterplan can be the easy bit to start with. Working out how you are going to get planning consent and then deliver it on time and in budget is when it starts to become a lot more challenging.

“The masterplan is also about what you’re safeguarding, as well as what you’re building. Try to keep your options as open as possible, and make sure that the masterplan is used as a development tool to ensure that short-term decisions and opportunities don’t end up impacting the long-term strategy.”

A digital tool

The format of the average masterplan has undergone considerable change. “It used to be a coffee-table book,” says Jacobs’ Andrew Gibson. “Between perhaps 50 and 100 pages, beautifully presented with a nice hardcover that sat on the shelf at the airport, which you sent out to all your stakeholders, and updated every 5 to 10 years. But as masterplanning has got more complex, it’s becoming a digital tool that can help us make decisions as we go along.”

However, a digital masterplan should not be confused with an airport digital twin, warns Heathrow’s Ross Dickie. “They’re different things,” he explains. “A digital twin is a representation of your existing facilities, which enables you to interrogate a digital model rather than a physical airport.

“Unlike a digital twin, you would not expect the airport to communicate what’s happening in real time back to the masterplan. A digital twin is a model of something that exists or is being developed, whereas the masterplan is a vision for the future, describing infrastructure that doesn’t yet exist. A digital twin uses real asset data to help tactical decision making, whereas a masterplan looks forward up to 50 years so can include infrastructure that’s decades away from delivery.”

This article originally appeared in the April 2024 issue of Passenger Terminal World. To view the magazine in full, click here.