IATA’s aviation security director, Matthew Vaughan, considers how the security landscape continues to shift two decades on from the tragic events of 9/11

How has aviation security changed since 9/11?

A great deal has changed – namely the focus on protecting the cockpit and carrying out passenger screening. Valuable improvements in technology for security screening and the sharing of advanced passenger information have helped governments and industry manage aviation security risk.

A great deal has changed – namely the focus on protecting the cockpit and carrying out passenger screening. Valuable improvements in technology for security screening and the sharing of advanced passenger information have helped governments and industry manage aviation security risk.

Unfortunately, we have also witnessed several isolated terrorist attacks and plots against aviation that were thwarted before aviation security measures were required. Terrorist interest in aviation has not wavered in the past 20 years, but the security measures have strengthened, targeted with eight amendments to ICAO’s Annex 17 baseline of standards and recommended practices for international aviation security, in the time since 9/11.

What are the main security threats to airports, currently?

The big one is still the insider threat [i.e. the threat posed by employees who have access to privileged information, aviation assets or airport premises]. As such, stringent background checks and regular screening of staff remain critical. Covid-19 has potentially aggravated this state, with an estimated 40% of the pre-Covid aviation workforce no longer in aviation, meaning there’s a lot of operational knowledge currently outside of the proverbial aviation perimeter. Without directly inferring that former staff are at risk of exploitation, there is a higher significance of risk-based security controls for operators to minimize the likelihood of insider threat-related occurrences.

And then there’s the potential threat that passengers present to aviation. Twenty years after 9/11, this is still a major concern, remaining front and center of airport security planning and how best to prioritize and fund the specific controls needed to continuously improve security.

The 2017 Islamic State Sydney plot [where two brothers in Sydney, Australia, guided by Islamic State operatives in Syria, plotted to bomb an Etihad airplane flying from Sydney to Abu Dhabi carrying 400 passengers, before being arrested] highlights how we must always remain vigilant, ensuring the best possible explosives detection and baggage screening capabilities are available and in line with international standards.

We’re also seeing the emergence of several integrated risk vectors, from technologies introduced at airports to increase efficiency or manage risk to continuity, optimization and service, such as drones and robotics. Such innovations require certain vulnerabilities to be managed through the adoption of appropriate ‘cybersecurity-by-design’ principles.

What impact has the pandemic had on aviation security?

Access to new levels of funding and incentivizing the R&D required for next-generation screening are tough right now. There are revenue concerns that need to be addressed before airports can get into looking at what those new funding priorities should be. However, 20 years after 9/11, the security controls in place at the gateways that carry 90% of the world’s passengers really are the best that they can be, especially with regard to explosives detection, despite the current revenue-challenged environment. Looking forward, we’re already working on the investment case for the next five years and beyond, to ensure airports can respond to the threats of tomorrow, and we have every confidence that will be the case.

In terms of the passenger experience, even prior to Covid-19, aviation security was challenging. The passenger journey was complex and could be incredibly varied, with passengers never certain if they would need to remove their shoes, jackets and laptops. But if you ask a hardened security expert, this is exactly how it should be – in other words, the last thing you want is any predictability in the security process. You need to know on the day that you could be subject to a variety of controls. The unpredictability is a vital post-9/11 defense measure. So it’s about finding that balance.

Covid-19 has unfortunately added a new layer of checks and balances that are going to take time to achieve maturity and reliability, with questions remaining around the effectiveness of certain procedures. Inevitably, these checks are going to be subject to stress, particularly as demand surges as more and more passengers return to the skies, with a four-hour processing window not unheard of.

At the end of the day, every airport is seeking a facilitated security process capable of performing the baseline measures according to international obligations, while also looking to reduce irritation by getting people that are trusted through the system with as little intervention as possible.

How do you feel the current situation might be improved?

How do you feel the current situation might be improved?

There are some conversations taking place, certainly within the US, on whether security staff should be carrying out health measures at a more integrated checkpoint that looks at both health and security at the same time. As an airline association, we don’t currently have enough information/analysis to determine the correct and/or preferred way forward on this, but we are aware of airports and jurisdictions that are looking at what’s feasible from a legislative/regulatory viewpoint, and what is not.

The other big elephant in the room is the potential offered by biometrics. In terms of a near-contactless, more seamless experience in relation to security and health protocols, biometrics allows you to do a whole bunch of things with just the presence of your face [or another biometric token]. Certainly, the pandemic has served to accelerate interest in its application, but the technology is also vulnerable to privacy and cyber-related concerns, so it’s going to take time to assess, and IATA itself continues to road test the associated strategies, through both its One ID and IATA Travel Pass (ITP) initiatives.

It’s poignant to note that biometrics was one of a number of 9/11 Commission report recommendations – but two decades on, we’re still piloting exit and entry biometrics in the US, as it remains such a profoundly sensitive subject. However, for most business travelers, it’s true to say that if it means they can get to the aircraft more quickly, without being irritated, it’s a case of ‘do what you need to do’.

Looking forward, it’s clear that current health checks are going to remain a critical issue. That’s why we have developed the ITP to ensure passengers are in control of their data and can more easily facilitate the sharing of their test results with airlines and authorities for travel. Ultimately, we want to make it more convenient for passengers and airlines to manage travel documentation throughout their journey. The goal is to get to a point where it’s about passenger-to-government data exchange, as and where applicable.

Any other changes you’d like to see?

We still have boarding gate checks – often called ‘secondary measures’, which airlines continue to pay for. There are some open, and there are some classified, reasons as to why certain governments have regulated activities in this way. However, it’s clear these secondary measures continue to impact efficiency while adding cost to the airlines, and ultimately passengers. You must question what’s going on that you believe that the primary security layer needs to have such a backstop. So, if there’s one thing I’d like to see improved straight away, it’s the policies around secondary measures.

Beyond that, I’d just like to see more security awareness – with everyone from the screener at the checkpoint all the way up to the airport CEO having a very acute understanding of the key issues. Hence, I was particularly pleased to hear ICAO had decided to extend its Year of Security Culture initiative to 2021. Now, more than ever, it’s critical to remain alert and continue to emphasize the importance of security measures alongside necessary health checks.

Cyber – the new front line

An ever-increasing reliance on data and connectivity continues to exacerbate cybersecurity risks – 20 years on from 9/11, airports and airlines must ensure both physical and digital assets offer the highest levels of protection against attack. IATA’s Air Transport Security 2040 and Beyond white paper on security warns that cyber threats are likely to evolve from low-scale ‘nuisance’ incidents to far more sophisticated attacks that could cripple whole aviation networks.

Currently, most critical security infrastructure and systems are run locally at airports, often on different networks to other airport systems. However, IATA warns that by 2040, more and more services and processes will occur off airport, remotely, or online, necessitating connectivity with a wider range of public and private networks. This will exponentially increase the possible attack paths available to those seeking to infiltrate and exploit the system. The white paper suggests terror groups could choose to hack x-ray or CCTV systems, for example, to allow its members or prohibited objects to pass through uninhibited.

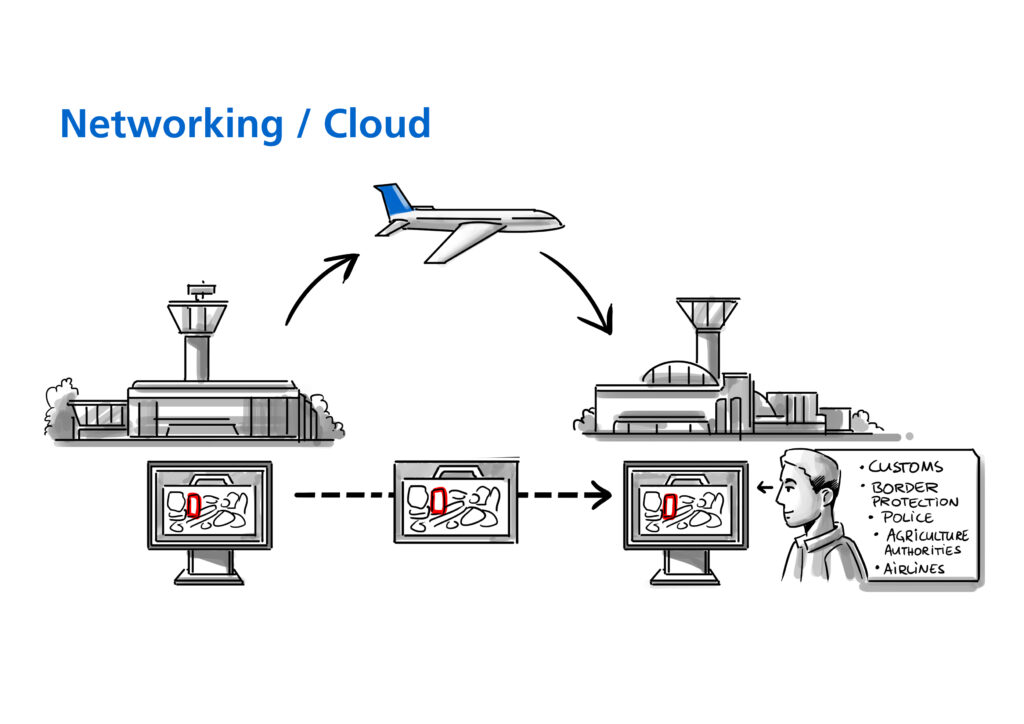

Hold baggage screening (HBS) devices and passenger and carry-on baggage scanners that collect often highly sensitive data are at particular risk. A move toward centralized image processing away from the checkpoint has seen screening equipment become increasingly connected to improve efficiency and enable information sharing between security officials to help tackle potential threats. However, this also makes it more vulnerable to cyberattack.

Richard Thompson, global director of aviation at Smiths Detection, warns the financial pressures brought by the pandemic will only speed this trend: “Lots of airports are trialling third-party AI-enabled algorithms to analyze images to see if they can do an even better, more efficient job that involves employing fewer people, to manage their costs more effectively,” he notes. “These algorithms rely on data being shared through an open architecture, and potentially via the cloud. However, if not implemented responsibly, open interfaces with third parties could reduce a screening system’s overall robustness to a cyber threat.”

To prevent sensitive data falling into the wrong hands, airports must ensure the safe custody of x-ray images when transferred between authorities: “Collaboration is key to open architecture – only together can we make aviation safer and more efficient,” notes Thompson. “Cyber threats are increasingly sophisticated and no one is safe from attacks. Threats can be internal or external, deliberate or unintentional, so it’s important to take a holistic approach to cybersecurity, developing policies and a culture that considers not just hardware but people, processes and technology. From the outset, we work with customers to understand their operational risks and compliance requirements, to help them develop robust policies. Cybersecurity is an ongoing process. By establishing flexible and robust foundations, organizations will be able to adapt to new and developing threats.”

This article was first published in the September 2021 edition of Passenger Terminal World magazine, which you can read online, now, for free, here.