No part of the airport experience has been left untouched by the impact of coronavirus. In the case of the security screening process, a new raft of measures are being brought in to minimize passengers’ contact with both security staff and other travelers.

In the USA, for example, the TSA introduced new rules in May requiring all travelers to wear face masks, scan their own boarding passes and pack carry-on food separately from their luggage in a clear plastic bag. Similar rules have been brought in at airports worldwide, as well as the introduction of floor markings to ensure travelers socially distance while queuing to be screened.

But the introduction of physical distancing requirements in security screening is likely to have severe impacts on a process already beset by bottlenecks and over-capacity issues.

The fact that it hasn’t done so already is only because passenger numbers remain at such an unprecedented low, according to Billy Shallow, manager of the Airports Council International’s (ACI World) Smart Security program, an initiative that explores future solutions for achieving a seamless airport security screening experience. But as the numbers recover, Shallow believes that the social distancing measures will become increasingly unsustainable.

“ACI is advocating physical distancing where appropriate,” he says. “However, we carried out some analysis, which showed that if passengers are physically distancing in a queue, airports can only operate their security checkpoints at about 30% capacity. Realistically, you can’t design checkpoints to operate at 30% capacity. So while these measures are necessary at the moment, as soon as traffic numbers start to grow we have to come up with other concepts.”

Pre-booked security

One solution already being trialled since June at the UK’s Manchester Airport has been the introduction of a security booking system. The system developed in-house by airport operator Manchester Airport Group’s (MAG) digital arm, MAG-O, allows travelers to go online and pre-book a free 15-minute security slot. This way they can avoid queuing by gaining access to a dedicated lane that takes them straight to the security checkpoint.

“The way we thought about it when we were conceiving it was similar to how people book times for grocery deliveries,” explains Simon Butterworth, MAG’s chief marketing officer.

The system enables the airport to more easily manage the volume of passengers coming through security, both by re-directing a proportion of travelers away from the queuing area and into the dedicated lanes, and also because of the extra insights the new data source provides.

“In the past we knew when flights were going out, but we didn’t know in advance when individuals and groups were going to turn up at security,” says Butterworth. “But by providing us with this data this system really enables us to manage the security queues operationally, by giving us insights as to when we can expect peaks and troughs in demand.”

Demand for the new service has far exceeded expectation, according to Butterworth, and MAG is considering expanding it to its other two UK airports, London Stansted and East Midlands.

Future visions

Other solutions that are being looked at by the industry are summarized in ACI World’s Smart Security Vision 2040, a report on future security solutions published in June by the agency as part of the Smart Security program.

While most of these technologies were being thought about before the pandemic, the greater degree of automation that they offer makes them suitable for the post-Covid-19 operational reality, notes Shallow, who authored the report. “A lot of focus will be on technology, advancing the algorithms and essentially reducing human contact,” says Shallow. “We expect the technology to be so good that humans will really only be there to conduct alarm resolution or to intervene where there’s a problem.”

Some of the technologies covered in the report include screening gateways – enclosed walkways that allow travelers to be screened along with their baggage in a single, seamless process. This contactless approach, also known as stand-off detection, would “screen for a magnitude of threats all at once as opposed to having to put your bag through an x-ray then you go through a walkthrough detector and then a body scan,” comments Shallow.

But it will be at least 15-20 years before the technology for the screening gateway is sufficiently matured for it to go into service, according to Shallow. In the meantime, he sees the development of self-service security systems as a good intermediate solution.

The systems could be operated by travelers in the same way as current automated kiosks for self-tagging checked baggage or printing boarding passes, relying on sophisticated algorithms to do the threat detection in place of security staff.

The idea is being taken seriously by the industry with the TSA putting out in May a request for information (RFI) from tech firms for a self-service concept that would accelerate “passenger throughput” while “reducing the overall level of contact a passenger experiences”.

Simulating changes

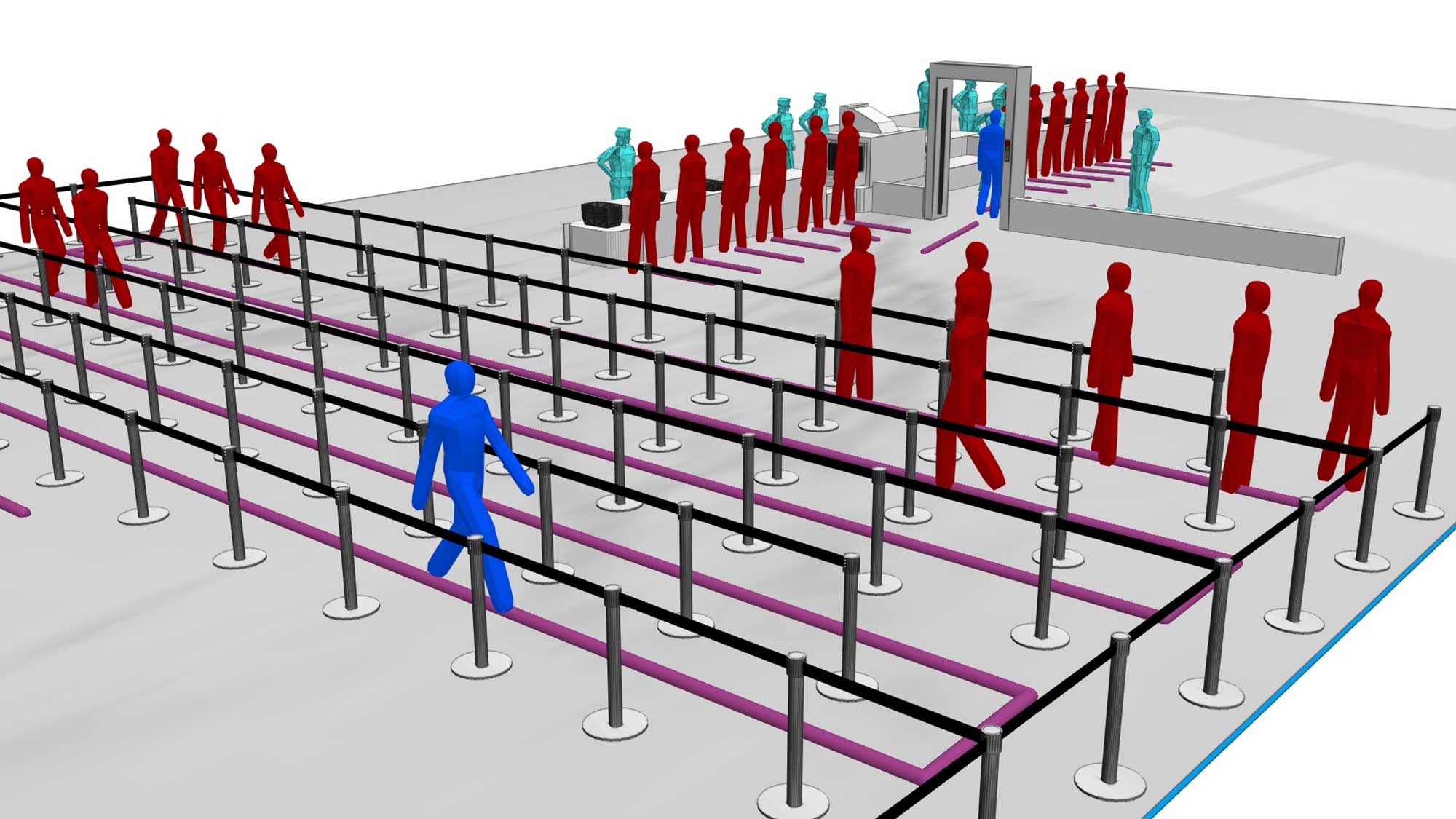

While the self-service kiosks are likely to see the light of day before the screening gateways, both concepts are still distant goals for an industry that is trying to grapple with the immediate implications of the pandemic on how it conducts its security operations. To answer these more pressing questions, airports are turning to software such as MassMotion, the crowd analysis tool developed by the design and engineering multinational Arup.

The software allows airports to run simulations that show how changes to security processes play out in real time. “It helps you easily visualize how a particular process change or a space change will manifest in real life,” says Stacey Peel, Arup’s global aviation security lead.

Since there is no limit to the simulations’ size or run-time, the tool can help airports see how changes to processes affect not only the screening area but the entire journey through the airport and beyond. This is important, notes Peel, because a lot of the changes introduced in the light of the pandemic have not taken into account the “flow-on effect” on the rest of the airport, passenger journey or staff movements.

“Often airports are looking at the process in isolation of the entire terminal journey,” says Peel. “But while the changes they adopt might address the physical distancing issue within the screening checkpoint, it’s important to realize they have flow-on effects for elsewhere in the facility.”

Measures introduced to facilitate physical distancing in the screening lane, for example, have “an impact on throughput, which then has an impact on processing time for the entire area in terms of displacing people back into the queueing space, which in turn displaces people back into the approach to the queuing area,” says Peel.

Moreover, the introduction of measures to limit contact between security staff and travelers and their baggage adds further delays. For example, while many instances of travelers triggering alarms could in the past have been resolved quickly with a pat-down, they now might require travelers to undertake further unassisted divestment and pass through detectors multiple times until they can resolve the issue themselves.

“In the short term, the macro process isn’t changing fundamentally, but it’s slower,” says Peel. “Also, the onus for being better prepared is being put back on the passenger. So there’s a passenger experience implication as well.”

Rethinking security

As airports come to terms with how physical distancing measures are affecting their security processes, as well as putting a huge dent in their capacity limits, Peel believes that they are reacting in radically different ways.

She explains, “I think at one end of the spectrum we’ve got airports who are

just gritting their teeth and saying, ‘We’ll just get through this and then go back to normal.’

“At the other end of the spectrum, we’ve got airports who are seeing this as an opportunity to completely rethink the whole screening checkpoint process, its design and the technology involved.”

For those airports interested in reinventing the wheel, it can provide an opportunity to introduce the long-elusive risk-based approach whereby screening measures are adjusted according to the risk the individual passenger poses. A similar approach has been advocated by ACI World through its Smart Security program. The appetite for such a fundamental overhaul of security exists in part because there is a growing recognition within the industry that the current model is flawed, notes Peel.

“There’s an underlying premise with the current model that every single person that is getting on board an aircraft has intent to attack. Therefore, you have to assess and deny every single person’s capability to facilitate an attack.

“But we know that’s not true. So why are we focusing on a person’s capability when in fact we should be looking at the intent of individuals, determining the threat and then managing the risk commensurately?” Peel adds.

But while many airports are keen to change things, and largely there is an ability to do so, the political will to switch to a more risk-based approach may not exist right now, according to Peel: “I think there’s a general acceptance that it will be challenging for regulators, and politicians in particular, to accept.”

With this in mind Peel thinks the most likely path forward will be one that introduces growing automation into existing technologies.

“So you might still use CT scan technology but you take humans out of the process and, for example, use machine-learning to support the threat detection instead,” she explains. “So the detection technology won’t change but how airports do their interpretation and decision-making is a bit more radical than what we have today.”

This article was originally published in the September 2020 issue of Passenger Terminal World.