While the COVID-19 pandemic affects seemingly every aspect of our lives, it’s worth remembering that it isn’t the first global disease we have had to tackle. In the June 2019 issue of Passenger Terminal World, we looked at what airports could do to stem the spread of communicable diseases:

In March a 23-year-old flight attendant found himself falling ill on a Cathay Pacific flight between Hong Kong and Tokyo. After returning to Hong Kong he was hospitalized at the city’s St Paul’s Hospital, having been diagnosed with measles. The disease is highly contagious and in little more than a month 29 workers at Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) had been infected.

Outbreaks like this are hard to avoid in an era of unprecedented global air travel, according to Angela Gittens, director general of ACI World. “Airports are acutely aware of the issue of disease control. It is a challenge that is inevitable with the rate at which air traffic is increasing and new routes are opening,” says Gittens, adding that airports need to incorporate disease control into their business continuity plans.

In line with Gittens’s advice, HKIA had in place “standing procedures and contingency measures for responding to infectious diseases” prior to the current outbreak, a Hong Kong Airport Authority spokesperson told Passenger Terminal World.

The preparedness plan enabled the airport to take several important measures to contain the outbreak. They included stepping up the disinfection and cleansing regime at busy locations in the terminals, as well as providing an extra 120 disinfectant hand-rub stations.

HKIA also increased the circulation of the ventilation system in the terminal and used the public address system to remind passengers to keep a close eye on their own health, especially if they were coming from countries where outbreaks had recently been recorded – Asia was experiencing a measles epidemic at the time.

Working with the authorities

The steps HKIA took appeared to work, with no new cases of the illness reported after mid-April. All the measures were put in place in liaison with Hong Kong’s Department of Health (DoH). This last point is significant, according to Gittens, because in the case of disease control it is important to note that airports only play

a “supportive role”.

“The responsibility for management of the risk of communicable diseases at airports rests primarily with the local, regional or national public health authorities,” Gittens says. “Airports can provide the infrastructure and important support systems that can help facilitate the work these agencies need to do.”

One of the actions HKIA helped to support was a DoH-led effort to provide on-site vaccination and testing for airport staff. The widespread availability of vaccinations for many years has meant that measles has largely been eradicated from most Western countries. But this is not the case elsewhere, according to Dr Gary Brunette, chief of the travelers’ health branch at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“There’s a term we use: herd immunity. It refers to the fact that if you have a vaccination rate over a certain percentage it will protect the community as a whole from an outbreak,” says Brunette. “But if your vaccination rates fall below that percentage then you give the pathogen the opportunity to spread. That’s the situation in many countries around the world where the measles vaccine is either not required or vaccination rates are very low.”

In spite of these factors, an outbreak of measles or any other infectious disease at an airport is extremely rare. This is because the incubation period for infectious diseases can run to several days, meaning that the traveler is usually long gone before they begin showing symptoms.

“If they do get sick at the airport it probably means they were exposed to the illness elsewhere,” Brunette says. Of course, this is not the case for airport workers and so it is no coincidence that they were the source and the principal victims of the Hong Kong outbreak.

Incubator of illness

For disease control experts, of far more concern than a full-blown outbreak is the risk airports pose as a repository for illness. “Any venue where you have a large number of people congregating has the potential for translating disease,” says Brunette. “The thing about airports that makes them more challenging than a shopping center, for example, is that you’re getting people from many places, which means you get a mix of viruses and bacteria in the environment.”

During the peak flu season in the winter of 2015/2016, the role of airports as incubators of illness was investigated by a team of British and Finnish researchers, who collected samples of air and from frequently touched surfaces at Helsinki-Vantaa Airport.

During the peak flu season in the winter of 2015/2016, the role of airports as incubators of illness was investigated by a team of British and Finnish researchers, who collected samples of air and from frequently touched surfaces at Helsinki-Vantaa Airport.

The study focused on the flu virus, but researchers were really interested in trying to understand how a future pandemic might spread through an airport. “Our idea was that if there is a pandemic it’s highly likely that we’ll find the pathogens in the same places that we find the ordinary influenza virus, as they spread in the same way,” says lead researcher Ilpo Kulmala, from Finland’s VTT Technical Research Centre.

Kulmala’s team used cotton swabs to take surface samples from various points in the terminal, including the plastic luggage trays at airport security, self-service check-in screens, handrails and toilet door handles. Air samples were also taken, as the influenza virus can be spread through the air.

They found that half of the trays in security harbored at least one respiratory disease, such as influenza or the common cold. Other areas where the virus was found in large concentrations were in the children’s play area and on card reader key pads in retail stores, especially in the pharmacy.

“This makes sense because there were probably a lot of sick people going to the pharmacy,” adds Kulmala, who carried out the study under the auspices of PANDHUB, an EU-funded project that aims to help transportation hubs develop pandemic preparedness.

Preventive measures

The high level of contamination that the study uncovered might be cause for concern, but Brunette says there are some practical steps travelers and airport staff can take to reduce

the risk of getting sick.

“We advise travelers to wash their hands frequently – it’s a very effective way of preventing the spread of disease. If you can’t wash your hands, use an alcohol-based sanitizer. And if that’s not possible then don’t touch your eyes and mouth.”

He also advises staying up-to-date on routine vaccines and thinking twice about traveling if you are sick. “It’s about being community-minded, because you are probably going to spread it to other people.”

In the case of a full-blown outbreak there are other measures that can be taken, according to Kulmala. “The World Health Organization advises that staff in an affected area carry personal protection devices, such as face masks and hand disinfectants. But airports are often reluctant to bring in measures like this because it can cause alarm among travelers.”

As well as alarming travelers, Brunette believes that face masks don’t actually work. “You would need a really advanced breathing apparatus to cut everything out,” he says. “That’s not the case with face masks.”

He is also dubious about the effectiveness of passenger health screening, another preventive measure advocated by both the WHO and ACI World. In the response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, several major hubs, including London Heathrow, introduced screening of travelers arriving from affected areas. At Heathrow, passengers were asked to fill out a health questionnaire and their temperatures were taken.

“It’s not a very effective use of resources,” says Brunette. “You might screen hundreds and thousands of people to potentially find one person.”

Kulmala’s British partners in the PANDHUB project – researchers from the UK Department of Health – evaluated the effectiveness of screening, drawing similar conclusions to Brunette. Kulmala adds, “Because the incubation period for these diseases is so long, unless you are showing symptoms at the time it’s likely that you will evade the monitoring even though you are a carrier.”

Other technologies Brunette and Kulmala are lukewarm about are thermal scanners and infrared thermometers. This is not only because infected travelers showing no symptoms are likely to be missed, but also because of the risk of false positives for travelers who might simply have become hot through rushing for their flight.

Atlanta’s Hartfield Jackson International Airport, meanwhile, has fitted its bathrooms with smart sensors that tally the number of travelers going in and trigger an alert to staff when the facility is due for a clean.

Self-cleaning tech

While the jury is still out on many of the current prevention methods, a number of other technologies are being looked at.

Ohio’s Akron-Canton Airport has begun trialling self-cleaning mats that can be added to security trays. Known as nanoseptic mats, they use a self-cleaning oxidation reaction to break down contaminants on the trays. The mats were created by US tech firm NanoTouch Materials, which is developing the technology so that it can be added as a film over the touchscreen pads on self-service check-ins and in-flight entertainment systems.

Kulmala says the effectiveness of the nanoseptic mats would depend on how quickly they kill the pathogens. “If an infected person spreads the virus onto a tray, the antimicrobials would have to work fast because tray circulation time is quick and someone else will be using that tray shortly afterward.

“Another problem with these antimicrobials is that they are working when they are not needed. The microbes they kill are part of the human biota, meaning some of them are useful and necessary for our health.”

————————————————–

Why good coughing etiquette is vital in disease control

Coughs and sneezes spread diseases – we learn this in the playground. When you cough you disperse droplets into the air. If you are sick then these droplets will contain pathogens that can infect anyone else who happens to inhale them.

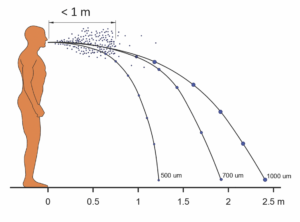

The path to infection depends on the size of the droplets, according to Ilpo Kulmala of the VTT Technical Research Centre in Finland. “Bigger droplets fly quite far but settle down quickly; smaller droplets can remain airborne for quite a while,” he says.

Increasing the circulation of the ventilation system – as was done at Hong Kong International during the recent measles outbreak – can help to remove some of the smaller droplets from the environment, according to Kulmala. However he says it is unclear how much of an impact this can have.

“Scientists are still debating just how much of a factor airborne droplets are in spreading disease. The current thinking is that it is most commonly spread by larger droplets, but it certainly doesn’t do any harm to increase the ventilation.”

Pathogens in the larger droplets commonly find their way into the body through someone touching a surface they have landed on. Therefore, while it makes sense to steer clear of a seat where someone has just sneezed, you will usually have no way of knowing that the pathogen is present in the environment.

Pathogens in the larger droplets commonly find their way into the body through someone touching a surface they have landed on. Therefore, while it makes sense to steer clear of a seat where someone has just sneezed, you will usually have no way of knowing that the pathogen is present in the environment.

The measles virus, for example, can stay active for up to an hour, according to Gary Brunette, of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, meaning that “you can be infected long after the person who spread the virus left the room”.

“So one simple measure for stopping the spread of infection is observing

good coughing etiquette,” says Kulmala. “We have run simulations and it’s very clear that if you cover your mouth and nose when you sneeze it dramatically reduces droplet dispersal.”

————————————————–

Best practice for airports during an outbreak

Keep the public informed. Airports have a number of avenues available to them for ensuring the traveling public is kept up-to-date, according to Angela Gittens of ACI World.

During an outbreak this could include “prominent signage to inform passengers about risks, risk avoidance, symptoms associated with the disease and when and where to report should these symptoms develop”. She also suggests “educational posters or electronic displays on best practices such as hand-washing”. However, Gittens stresses that such public information campaigns need to be done in close collaboration with the relevant health authorities to ensure “all outgoing communications are fact-based”.

Keep congestion to a minimum. According to Ilpo Kulmala of the VTT Technical Research Centre, the level of transmission of infectious diseases such as influenza is directly proportional to the proximity of people to one another. “This is why a crowded commuter train is a much riskier proposition than a shopping center,” he explains. During an outbreak he suggests airports could help reduce congestion and therefore transmission by opening more lanes at check-in and security.

Step up your cleaning regime. Dr Gary Brunette, of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says “good protocols around hygiene” are a must at any time but particularly important when there’s an outbreak. During the Hong Kong International measles outbreak the airport “stepped up disinfection and cleansing at busy locations in the terminal buildings”, says a Hong Kong Airport Authority (HKAA) spokesperson.

Be aware of high-risk groups. A good example of this awareness occurred during the recent Hong Kong outbreak, when the airport authority brought in protective measures to ensure the safety of pregnant airport staff. This is because contracting measles during pregnancy is extremely dangerous for the developing fetus. The HKAA spokesperson says, “We sponsored them to undergo serology tests to confirm their immunization status, and allowed pregnant staff to work from home if it was agreed by department heads.”